Avenues for Justice

100 Centre Street, Room 1541

New York, NY 10013

info@avenuesforjustice.org

A year and a half into serving as Executive Director of Avenues for Justice (AFJ), I find myself returning repeatedly to one core principle: if we want fewer young people in detention, we have to start telling the truth about the real issues impacting their lives and factors propelling them into the criminal justice system.

Too often, the debate around youth justice focuses on stereotypes, soundbites, or scapegoating narratives. Instead of naming systemic failures, the conversation blames the very young people most harmed by those systems. If we truly care about public safety and community well-being, we must move past deficit-based language and confront the barriers that Black and Brown youth navigate every day throughout New York City.

Why Language Matters

For decades, nonprofits, including AFJ, have used language like “at-risk youth”. At first glance, these words might seem harmless or even compassionate. But I’ve grown to recognize they fail us in two important ways.

First, this language places the focus on the young person, not the system. It implies that they did something wrong and are now being given grace. That framing ignores the deeper truths: too many young Black and Brown people are born into communities facing socio-economic challenges, that remain underfunded exposing them to inadequate educational systems, violence, food insecurity, subpar healthcare, limited employment, housing options, and over-policing. Many carry trauma long before they ever encounter the courts.

Second, this language does little to educate the public. Most people outside the nonprofit world don’t even understand what “at-risk youth” means. The reality is that some of our young people are simply navigating survival in neighborhoods where opportunities are scarce and systemic barriers are high.

We need a different approach. Asset-based framing positions strengths as reasons for investment. It acknowledges resilience, creativity, leadership, and survival skills as the foundations for solutions. Instead of saying “at-risk youth,” we can say “youth navigating systemic barriers.” Instead of talking about “second chances,” we can talk about “expanding opportunity” or “course correcting”.

Words matter. Narratives matter. They shape how policymakers make legislative decisions, how donors give, and how the public understands the young people in our care. If we want to dismantle stereotypes, we must start with the language we use.

The Facts on Raise the Age (RTA)

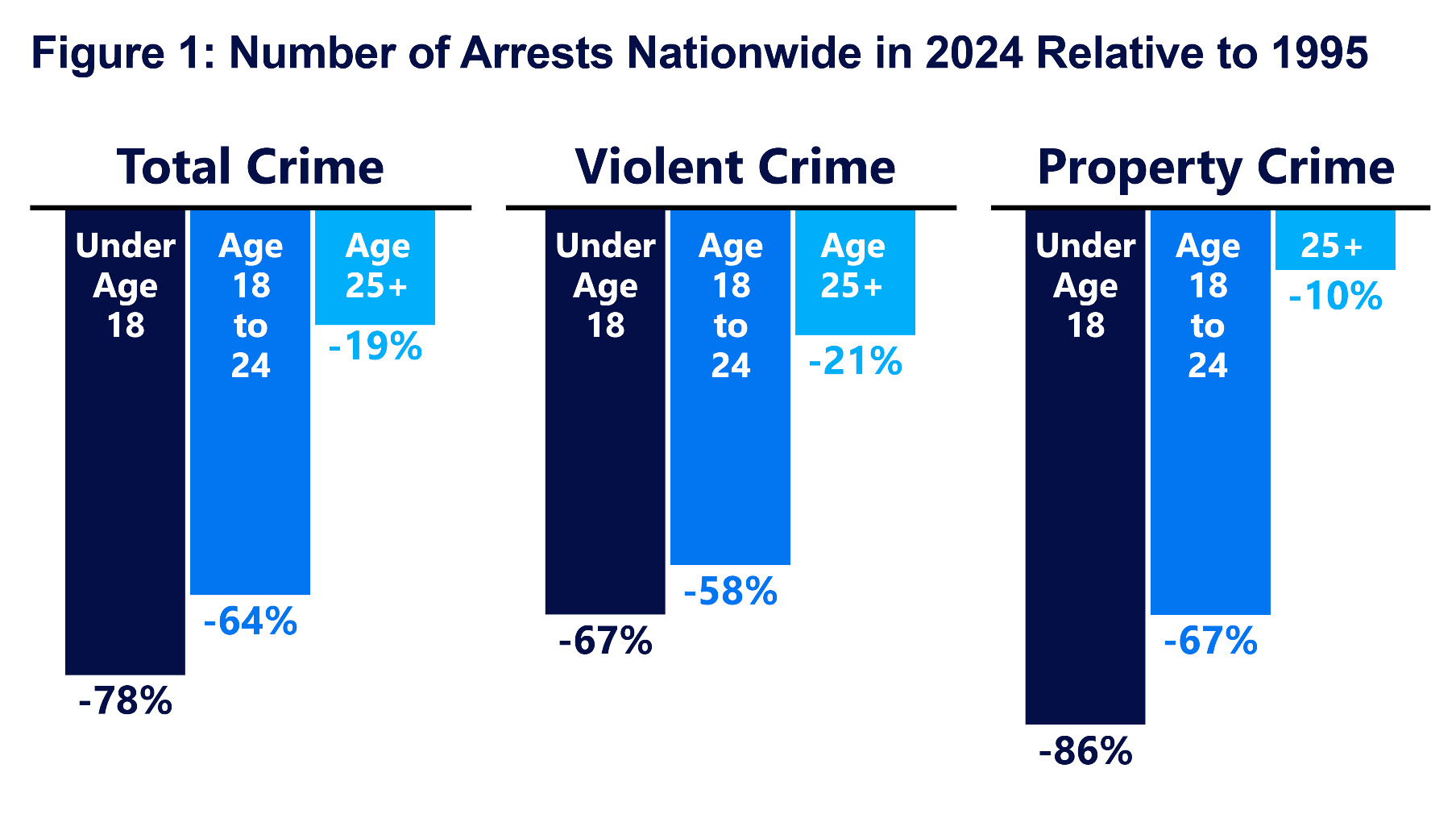

Right now, the conversation around youth justice in New York is deeply polarized, especially when it comes to Raise the Age (RTA). Some claim RTA has fueled violence, increased crime, increased recidivism rates or allowed young people to “get off easy.” These claims are simply inaccurate.

Here are the facts:

In other words: RTA is not the problem. The problem is what happens afterwards.

While it’s true that there are too many young people in detention facilities across the state, the real issue is not RTA itself, but how resources are distributed to support its success.

This year, the Governor’s proposed state budget includes $250M for continued RTA implementation. That represents an important commitment — but for it to make a real difference, those funds must flow more directly to impacted communities in New York City. And the process for organizations like AFJ, who are already proven alternatives to incarceration providers, needs to be more accessible and streamlined.

When funding reaches the ground in this way, it not only strengthens community-based programs, such as ours, but also fulfills the promise of RTA: safer communities, reduced incarceration, lower recidivism, more access to resources for the communities which most need it and brighter futures for youth and young adults.

Focusing on the Real Issues

Here’s the truth: Black and Brown young people in New York City are not struggling because of Raise the Age. They are struggling because they are profiled. They are struggling because they attend overcrowded and underfunded schools where teachers are doing the best they can with very few resources. They are struggling because their families live with the daily stress of generational poverty. Because their communities are saturated with violence, trauma, and too few opportunities for growth. If we want to change outcomes for young people, we have to stop blaming RTA and start focusing on the real barriers in their lives. That means investing in community-based organizations, rethinking our language, and dismantling stereotypes that do nothing to move the pendulum forward.

A Call to Action

So where do we go from here?

The lives of Black and Brown young people in New York City are shaped not just by the choices they make, but by the systems they are forced to navigate. If we want safer communities and more just futures, our focus must be on truth, investment, and opportunity — not stereotypes and scapegoating rhetoric.

At AFJ, we know what’s possible when young people are given services, not cells; when incarceration is the alternative, and not the norm. It’s high time our systems and our society catch up!

With sincerity,

AFJ Executive Director

Elizabeth Frederick